by Prof. Dr. Srithar Rajoo

Edited by Dr Zuhaili Idham

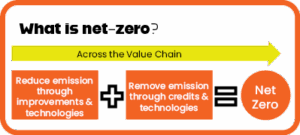

Climate change mitigation and the drive to Net-Zero are the main agendas for many governments in the world, including Malaysia. Malaysia is committed to achieving Net Zero status by 2050, while ensuring our economy and citizens continue to prosper healthily. The transport sector is one of the biggest emission producers in ASEAN, with about 310 million tons of CO2. As for Malaysia specifically, the transport sector contributes about 65 million tons of CO2. Interestingly, almost half of this emission comes from diesel engines, which dominate the heavy-duty sector.

The transport sector has been for more than a century being powered mainly by the internal combustion engines. It is not only the transport sector, but internal combustion engines have been the key powerhouse for many other sectors, which drove the economic growth we experienced in the past many decades. Sadly, climate change urgency has demonised the internal combustion engines for their significant pollution contributions. However, it is the fuel that contributes to all the pollution by combustion, and the machine itself is a time-tested engineering marvel. Hence, changing to a cleaner fuel with an internal combustion engine should be one of the pathways to a wider consolidated approach toward achieving Net-Zero. Hydrogen is a key source of zero-carbon fuel, which can power our lives through internal combustion engines. Hydrogen burns cleanly, combining with oxygen to produce water vapour as the primary byproduct. When used in a modified internal combustion engine (H2ICE), it offers the ability to reduce or eliminate carbon emissions while retaining much of the existing manufacturing base, supply chain, and mechanical familiarity of traditional engines. This positions the H2ICE as a viable replacement for the millions of conventional engines across many sectors.

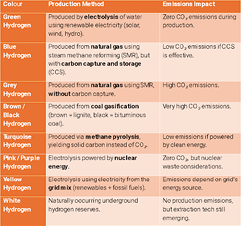

One may ask if H2ICE could replace all the conventional engines out there for a zero-carbon future. The answer is an obvious NO, as one should consider the life-cycle carbon footprint rather than just the tailpipe emission. This brings us to the question of how hydrogen is produced, and this is reflected in the many colours of hydrogen classification. Zero life-cycle carbon hydrogen fuel, such as green and pink hydrogen, is associated with a higher cost, leading to unfavourable total cost of ownership (TCO) and slowing down the adoption rate. If we focus on the passenger and light-duty vehicles, battery electrification offers much more attractive life-cycle carbon mitigation potentials. Considering the evolution of battery technologies and increasing renewable mix in the electricity grid, it is evident that drivers’ acceptance and life-cycle carbon will continuously improve with time. Hence, the passenger and light-duty vehicles should be a combination of battery electric and hybrid vehicles.

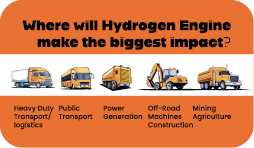

When we focus on heavy-duty applications, this is where H2ICE will shine. Considering the high and harsh demand of the application, the heavy duty sector is dominated by diesel engines. Battery electrification of the heavy-duty sector is doable and has been demonstrated in some cases. However, looking into the life-cycle carbon footprint of the significantly large battery capacity requirements and the high operational demand will prove this to be unsustainable, not to mention the cost to replace all the diesel assets and operate in a whole new electrified architecture. Hence the alternative zero or low carbon fuel pathway is most likely the realistic approach to decarbonize the heavy-duty sector such as logistics, public transport, power generation (mostly gen-sets) and off-load applications. In this scenario, the choice of hydrogen does not necessarily need to be green or pink with zero carbon footprint. Life cycle carbon footprint evaluation will show that blue, turquoise or white hydrogen could give favourable carbon mitigation plans, compared to full electrifications. Furthermore, the cost of adoption and operation could be very attractive as this utilises the existing assets with modifications. The existing diesel engines could be operated with dual fuel diesel-hydrogen as a mid-way strategy. This could be a transitional pathway before moving into a dedicatedly designed and developed hydrogen engine.

As with any solution, H2ICE comes with its own challenges. Hydrogen as a fuel for the mass faces challenges in production capacity, fuel storage, distribution infrastructure, cost parity and safety. As with the engine operating on hydrogen fuel, there are challenges for fuel supply system, combustion control, high boosting demand, material embrittlement, lubricant emulsification and nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions control. Hydrogen is the lightest gas that has high energy content by mass, but significantly low energy content by volume, compared to gasoline and diesel. To put into perspective, per Kg of hydrogen is about 3 times more energy dense compared to gasoline and diesel, but per litre of hydrogen is almost 6 times lower energy dense. Hence hydrogen is transported either in the form of gas at high pressure, upwards of 200bars, or in the form of cryogenic liquid. For the H2ICE, the hydrogen fuel most likely comes in the high-pressure tank, however the combustion usage will be at lower pressure. Hence an efficient fuel delivery system needs to be developed, either hydrogen is injected directly into the cylinder or into the port.

Hydrogen combustion has many orders of magnitude higher flame speed compared to gasoline and diesel. Thus, injection strategy and combustion control are also key elements to be tuned for an efficient operation. Due to the high energy content and high flame speed, hydrogen must be combusted in a very lean mixture, which requires much more air intake compared to the equivalent gasoline or diesel engine. This demands a bigger capacity charge-compressor, compared to the equivalent gasoline or diesel engine. However, the turbine that powers the charge-compressor is faced with comparably lower enthalpy exhaust, as it mostly consists of water vapour. This makes a conventionally matched turbocharger not suitable for hydrogen combustion. Advanced matching needs to be established between the charge-compressor, turbine and the engine.

Long-term exposure to hydrogen creates embrittlement issues in the engine materials. Coupled to this is the fact that hydrogen is the lightest gas and easily leaks, demanding much tighter clearance in the engine design. This has a significant impact on the engine reliability and safety. Research is still underway in many places to find the most suitable materials or coatings to sustain the long-term exposure to hydrogen. Leaking hydrogen and the water byproduct in the combustion chamber will eventually contaminate the lubricant, resulting in emulsification. Thus, the lubricant in hydrogen engines degrades with a whole new characteristic compared to gasoline or diesel engines. We need to understand the lubricant degradation characteristics and potentially formulate a new lubricant that could reliably operate under a hydrogen combustion environment. Hydrogen as fuel does not carry any carbon molecules, hence its combustion is carbon-free. However, the nitrogen in the air will react with the oxygen during combustion to form nitrogen oxide (NOx), which amplifies at higher combustion temperatures inherent to hydrogen. Nitrogen oxides (NOx) are a damaging pollutant that needs to be mitigated, where emission regulation in most parts of the world demands NOx to be close to zero. Hence, the hydrogen engine needs a more severe NOx mitigation strategy. Existing technologies, such as Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR), could be deployed, but on the downside, they will add to the cost.

As we delve into the pros and cons of hydrogen engines, it is apparent that continued research and development are necessary, coupled with advancements in low to zero-carbon hydrogen production. This could position hydrogen engines as a vital component of the future low-carbon energy landscape. At the Institute for Sustainable Transport (IST), Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM), active research and development are ongoing to investigate the challenges of hydrogen engines and find solutions that will pave the way for carbon mitigation in the transport and energy sector. Institute for Sustainable Transport (IST) UTM has been recognised in 2025 as the Higher Institution Centre of Excellence (HICoE) by the Malaysian Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), with the focus on championing hydrogen engine research and development. IST UTM collaborates with partners around the world with strong hydrogen research capabilities, which augments the knowledge transfer and industry applications.